United States Ship Worden (DD 352)

Official History

|

||

|

|

|

- Class: Farragut

- Hull number: DD 352

- Radio call sign: NASF

- Displacement: 1,726 tons (1,565 metric tons)

- Length: 341’3" (104 meters)

- Beam: 34’2" (10.4 meters)

- Draft: 8’10" (2.68 meters)

- Speed: 36.5 knots (42 m.p.h. or 67.6 km/h)

- Peacetime Crew: 186

- War Cruise Crew: 220

- Armament: 5×5" guns, 4×.30-cal. machine guns, 8×21" torpedo tubes, 2 depth charges

The third Worden was laid down on 29 December 1932 at Puget Sound Navy Yard, Bremerton, Washington; launched on 27 October 1934; sponsored by Mrs. Katrina Loomis Halligan, the wife of Rear Admiral John Halligan Jr., commandant of the 13th Naval District; and commissioned on 15 January 1935, Cmdr. Raymond Earle Kerr in command.

After fitting out, Worden departed Puget Sound on 1 April 1935 for her shakedown cruise that took her first to San Diego and thence along the coast of Baja California and mainland Mexico to San Jose, Guatemala, and Punta Arenas, Costa Rica. The new destroyer then transited the Panama Canal on 6 May and steamed north to Washington, D.C., where on 17 May she embarked Rear Admiral Joseph K. Taussig, Assistant Chief of Naval Operations, along with a congressional party, for a cruise down the Potomac River to Mount Vernon.

Worden subsequently returned to the Washington Navy Yard where her guns were disassembled for alterations. She then shifted south on 21 May 1935 to the Norfolk Navy Yard in Virginia. In the ensuing weeks, the ship underwent voyage repairs at Norfolk. The yard work was broken once by trials and tests off Rockland, Maine, and completed in the early summer. She ultimately left the Norfolk Navy Yard on 1 July and spent the weekend of the Fourth of July at New Bedford, Mass., before setting her course for the west coast. After proceeding via Guantanamo Bay and the Panama Canal, she arrived back at the Puget Sound Navy Yard on 3 August.

After a post-shakedown refit at her builders’ yard, Worden shifted south to San Diego, reaching that port on 19 September 1935, and commenced four years of operations from there as a unit of Destroyer Squadrons, Scouting Force. She performed valuable duty as a training ship for the Fleet Sound School, San Diego, and conducted the usual tactics and type training evolutions in local waters and in maneuvers that took her from Seward, Alaska, to Callao, Peru.

She also participated in regularly scheduled fleet problems and battle tactics with combined forces of the United States Fleet in the Caribbean Sea and in the Hawaiian Islands. One of the highlights of her operations during that time came in the autumn of 1937. In mid-September — Worden, in company with Hull and escorting the aircraft carrier Ranger — voyaged to Callao, Peru, for a visit that coincided with the Inter-American Technical Aviation Conference at Lima. While Ranger proceeded independently homeward upon conclusion of her visit, the destroyers paused at Balboa, Canal Zone, before returning to San Diego.

The War Years

The coming of war in Europe on 1 September 1939 altered Worden’s somewhat idyllic pattern of operations out of San Diego. Five days after hostilities began in Poland, the Navy commenced its Neutrality Patrol duties on 6 September. On 22 September, the Chief of Naval Operations directed the Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet to transfer, temporarily, to the Hawaiian area two heavy cruiser divisions, a destroyer flotilla flagship (a light cruiser), two destroyer squadrons, one destroyer tender, an aircraft carrier and base force units necessary for servicing those ships. That dispatch marked the establishment of the Hawaiian Detachment — the forerunner of the ultimate basing of the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor.

Worden was attached to this new force, commanded by Vice Admiral Adolphus Andrews, whose flag flew on the heavy cruiser Indianapolis. On 5 October 1939, she sailed for Pearl Harbor with Andrews and his large “detachment.”

Worden worked primarily in the Hawaiian Islands over the next two years, interspersing her time at Pearl Harbor and its environs with regular periods of upkeep on the west coast. Intensive type-training and tactical evolutions in task force exercises and maneuvers kept the Hawaiian detachment busy while the world watched Japan continue a bloody undeclared war in China. Upon the conclusion of Fleet Problem XXI in the spring of 1940, the entire fleet was based in Hawaiian waters.

Pearl Harbor

On the morning of 7 December 1941, Worden lay in a nest alongside the destroyer tender Dobbin, receiving upkeep. She suffered no damage in the attack made by Japanese carrier-based planes that occurred on the “date that will live in infamy,” but one of her gunners, Quartermaster 3rd Class Raymond H. Brubaker, trained his .50-caliber Browning machine gun on a low-flying bomber and sent it splashing into the waters nearby. Within two hours of the commencement of the attack, Worden had gotten underway and was proceeding to the open sea.

Although in the operational plans for the attack Japanese submarines were supposed to pick off American ships as they emerged from Pearl Harbor, their attempts to carry out that mission failed dismally. The danger of enemy submarines, however, did exist; purported submarine sightings proliferated. Many depth charges churned the sea that December day and killed a great number of unfortunate fish.

Worden picked up a submarine contact at 1240 — well over three hours after the attack by the enemy aircraft had been completed — and dropped seven depth charges. That afternoon, the destroyer joined a task force built around the light cruiser Detroit, the flagship of Rear Admiral Milo Frederick Draemel. Searching the seas southwest of Oahu, Worden rendezvoused with the fleet oiler Neosho and escorted her to a fueling rendezvous with Rear Admiral Aubrey Fitch’s Task Force 11 built around the aircraft carrier Lexington.

While Neosho fueled the ships of Task Force 11 on the morning of 11 December 1941, Worden assumed a screening station on Lexington’s bow and the next night escorted Neosho away from danger when Dewey discovered what looked like a surfaced enemy submarine and went on the offensive. After having seen Neosho to a safe haven at Pearl Harbor, Worden returned to the open sea on 14 December as part of the covering force moving toward beleaguered Wake Island. Hampered by the indecision attendant upon an unexpected change of command at the top of the Pacific Fleet, the Wake Island Relief Expedition was recalled on the morning of 22 December 1941, and the island fell two days before Christmas.

1942

Worden returned to patrol and escort operations in the Hawaiian Islands; and, while thus engaged with the Lexington task force, twice dropped depth charges on suspected enemy submarine contacts off Oahu on 16 January 1942 and again six days later.

Detached from Task Force 11 on the last day of the month, Worden left Pearl Harbor on 5 February to escort the seaplane tender Curtiss and the fleet oiler Platte, via Samoa and the Fiji Islands, to New Caledonia, and reached Nouméa on 21 February. Three days later, when the merchantman S.S. Snark struck a mine in Boulari Passage, Worden went to her assistance, passing a tow line to the sinking ship and pulling her clear of the channel entrance. Worden’s medical department tended six injured men, and the ship brought the crew safely to port.

Departing Nouméa on 7 March 1942, Worden — in company with Curtiss — set course for Pearl Harbor and reached that port on the 19th. That day, the destroyer entered the navy yard there and, after her repairs had been finished, joined Task Force 11 on 14 April 1942.

Worden headed out to sea on April 15th, in company with the Lexington task force, bound for a rendezvous area southwest of the New Hebrides Islands, where on 1 May they joined Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher’s Task Force 17, built around the carrier Yorktown. On May 2nd, after the two carrier task forces had fueled, Worden was detached to escort the fleet oiler Tippecanoe to Nouméa. In her absence, the American carriers — in the Battle of the Coral Sea — blunted a powerful Japanese thrust toward Australia and the tenuous Allied supply lines and turned it away from strategic Port Moresby.

On 12 May 1942 — two days after she reached Nouméa — Worden was joined in that port by the cruisers and destroyers of the former Lexington task force. "Lady Lex" had succumbed to massive internal explosions and fires started during the battle. As part of that group, Worden put to sea on the 13th and, the following day, rendezvoused with Task Force 16 off Efate in the New Hebrides. Formed around the carriers Enterprise and Hornet, this force was commanded by Vice Admiral William F. Halsey.

Midway

Task Force 16 reached Pearl Harbor on 26 May 1942 to fuel and replenish stores on the eve of what seemed to be shaping up as a critical battle. American intelligence men had cracked enough of the Japanese fleet’s naval code to be able to determine the enemy’s future course of action and had picked up information which indicated that Japan planned a major thrust centering on Midway and including a diversionary strike in the Aleutians. Accordingly, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, took decisive action and prepared for what history would record as the turning point of the war in the Pacific — the Battle of Midway.

Worden sailed on 28 May 1942 with Task Force 16 — the force now under the command of Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, who had replaced Halsey. Later, Task Force 17 — formed around the hurriedly repaired and replenished Yorktown — rendezvoused with Spruance’s force to the north of Midway.

Worden screened Enterprise and Hornet throughout the Battle of Midway as planes from those carriers and from Yorktown turned back the Japanese armada from 4 to 6 June 1942.

South Pacific

Worden returned to Pearl Harbor on the 13th and was soon assigned to the screen of a revitalized Task Force 11, built around the newly repaired Saratoga. The destroyer escorted Saratoga as she sailed to Midway and flew off reinforcement groups of Army and Marine Corps aircraft before returning to the Hawaiian Islands for training.

On 9 July, Worden headed for the South Pacific with Saratoga’s task force but was temporarily detached on the 21st to escort Platte to Nouméa, reaching that port four days later. While Platte took on her vital cargo to replenish ships of the carrier task force, Worden patrolled the harbor entrance. On the 28th, Worden and Platte got underway to rejoin Saratoga.

En route on the first night out, Worden sighted signal lights in the darkness. She soon took on board 36 survivors of the sunken Dutch transport Tjinegara, which had been torpedoed on July 25th by the Japanese submarine I-169 and sunk about 75 miles southwest of Nouméa.

Worden returned to the Saratoga group to the south of the Fiji Islands on the following day, when the carrier forces joined marine-laden troop transports that had sailed from Wellington, New Zealand, for the invasion of the Solomon Islands. Her stay with the carrier was brief, for the destroyer was soon detached to escort the fleet oiler Cimarron to Nouméa, where she landed the Tjinegara’s survivors on 1 August.

Worden caught up with Task Force 16 on 3 August 1942 and, shortly before daybreak on the 7th, was screening Saratoga as the carrier launched air strikes against Japanese positions on Guadalcanal and Tulagi preparatory to the landings. Their efforts, together with those of the cruisers and destroyers, provided the coordinated shore bombardment which covered the 20,000 Marines who went ashore to begin the campaign that would — after six months of the fiercest fighting of the war — evict the Japanese from Guadalcanal the following February.

For the next two weeks, Worden operated with Saratoga south of the Solomons protecting supply and communication lines leading to Guadalcanal. During the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, Worden screened the flattop as she launched air strikes in company with Enterprise to sink the Japanese carrier Ryujo and damage the seaplane tender Chitose. Less than a week later, however, Japanese submarine I-26 torpedoed Saratoga and put her out of action, necessitating a trip to the mainland United States for repairs.

Worden screened Saratoga’s retirement via Tonga-tabu in the Tonga Islands to Pearl Harbor, arriving there on 23 September 1942. Five days later, she sailed with two other destroyers — screening the battleships Idaho and Pennsylvania — for the west coast of the United States.

She reached San Francisco on 4 October but departed again a week later with the destroyer Gansevoort to accompany Idaho to Puget Sound where they arrived on the 14th. Worden soon returned south to San Francisco and later joined Dewey in screening Nevada during her post-repair trials off Southern California.

Alaska & Loss

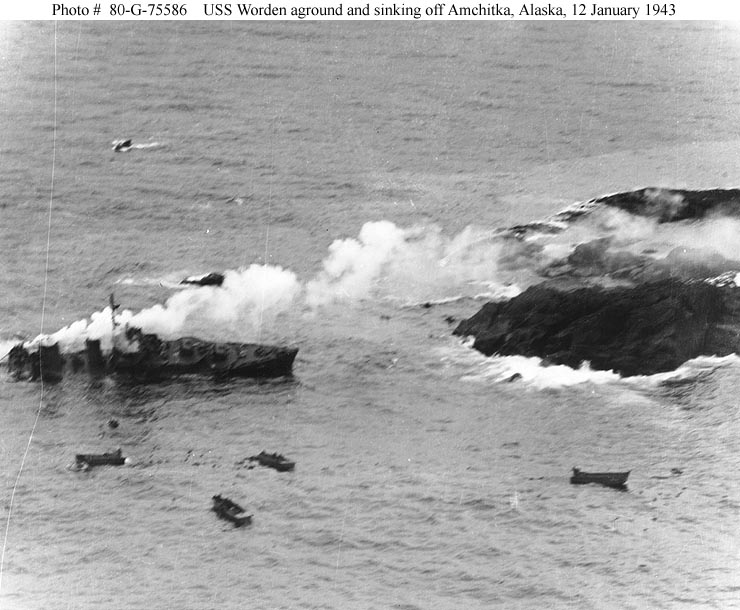

Two days after Christmas 1942, Worden sailed from San Francisco to support the occupation of Amchitka Island in the Aleutians. She reached Dutch Harbor, Alaska, on New Year’s Day 1943 and on 12 January 1943 was guarding the transport Arthur Middleton as that transport put the preliminary Army security unit on the shores of Constantine Harbor, Amchitka Island. The destroyer maneuvered into the rock-edged harbor and stayed there until the last men had landed and then turned to the ticklish business of clearing the harbor.

A strong current, however, swept Worden onto a pinnacle that tore into her hull beneath her engine room and caused a complete loss of power. Dewey passed a towline to her stricken sister and attempted to tow her free, but the cable parted and the heavy seas began moving Worden — totally without power — inexorably toward the rocky shore. The destroyer then broached and began breaking up in the surf; Cmdr. William G. Pogue, the stricken destroyer’s commanding officer, ordered abandon ship; and, as he was directing that effort, was swept overboard into the wintry seas by a heavy wave that broke over the ship.

Pogue was among the fortunate ones, however, because he was hauled, unconscious, out of the Bering Sea. Fourteen of his crew drowned. Worden was a total loss. Her name was struck from the Navy list on 22 December 1944.

[On 10 August 1943, the Navy destroyed the wreckage with four electrically detonated Mark VI depth charges in an effort to prevent salvage of the secret radar gear that had been installed in San Francisco.]

Worden earned four battle stars for her World War II service.

Battle Stars (with U.S. Navy star code):

- Pearl Harbor (P1) 7 December 1941

- Midway (P7) 3 to 5 June 1942

- Guadalcanal-Tulagi landings (P8) 7 to 9 August 1942

- Eastern Solomons [Stewart Island] (P11) 23 to 25 August 1942

Source:

U.S. Navy Historical Center