Loss of Worden, 12 January 1943

Constantine Harbor, Amchitka Island, Alaska Territory

A little before 8 a.m. on 12 January 1943, shortly after landing an advance security detail of nine Alaska Scouts and 30 other U.S. troops on Amchitka Island in the Aleutians, the strong current in Constantine Harbor swept Worden onto a pinnacle rock.

The Army detail was a sub-unit of the group known informally as Castner’s Cutthroats or simply the Alaska Scouts, but officially known as the 1st Alaskan Combat Intelligence Platoon (Provisional). The mission of Operation Crowbar was to determine if the Japanese were still on Amchitka, and exactly where.

Worden had drifted toward submerged rocks in almost total darkness. The moon was below the horizon and sunrise was not until 10:04 a.m. (20:04 UTC), so it was still pitch dark in the wintertime Bering Sea off Amchitka, making damage control efforts dangerous. Worden dropped anchor in an attempt to minimize grinding against the rocks, and briefly it helped.

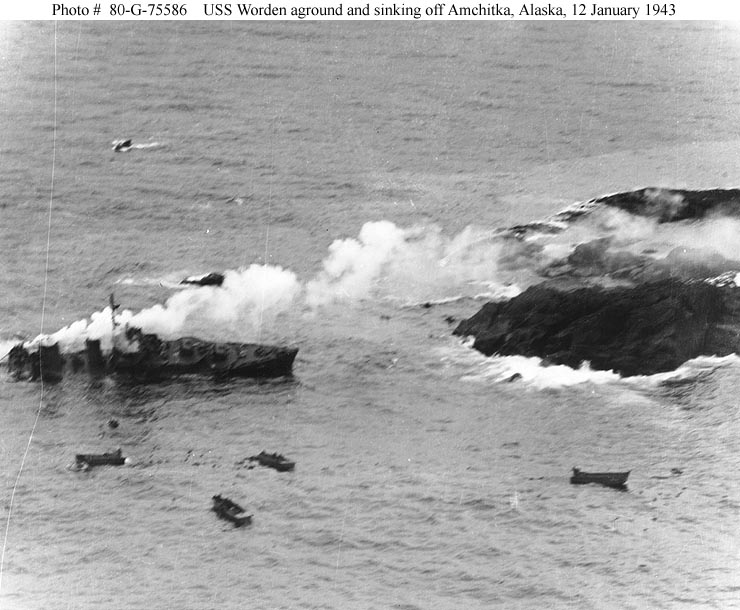

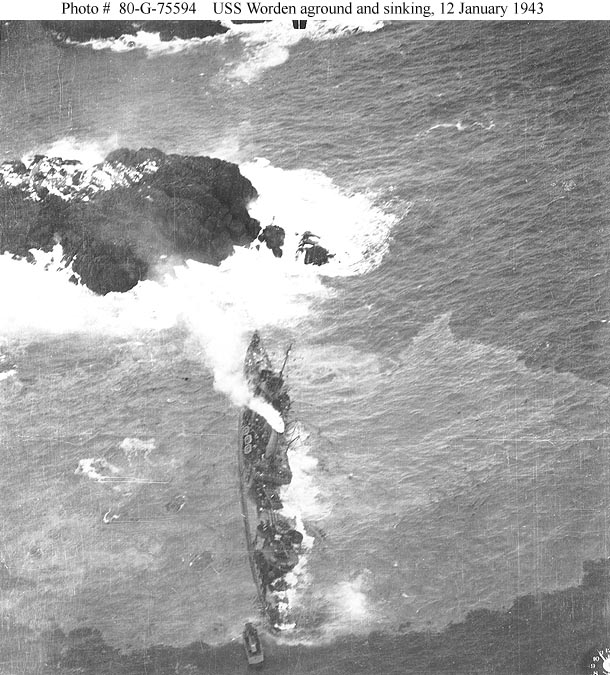

With its hull opened to the sea amidships and its engine room flooded, Worden was left without power. After daylight, its sister ship Dewey attempted to tow Worden to safety, but the line quickly snapped. Worden was immediately pivoted around by the current, grounded on an even larger rock outcropping and left at the mercy of the waves.

The water temperature was 36°F (2°c), and the air was much colder. With the ship listing heavily and the mid decks awash, Worden’s commanding officer, Lt. Cdr. William Grady Pogue, ordered abandon ship, and small craft from Dewey and the attack transport Middleton’s began to remove the crew. Before this work could be completed, Pogue and some of the crew men were cast overboard into the icy Bering Sea. Virtually all 14 deaths were caused by exposure; some of the sailors had jumped overboard in their underwear in the mistaken belief that the weight of their winter clothes would pull them under water.

Heroism abounded: Yeoman Second Class Paul Gillesse, the ships’s clerk, tied a bag of important documents to his foot and swam to safety. A crewman with a broken leg was rescued by two shipmates who refused to abandon him. The disbursing officer, Phil Barker, jumped into the water with $30,000 in cash. Rescuers earned seven Navy and Marine Corps Medals, the second-highest non-combat military award.

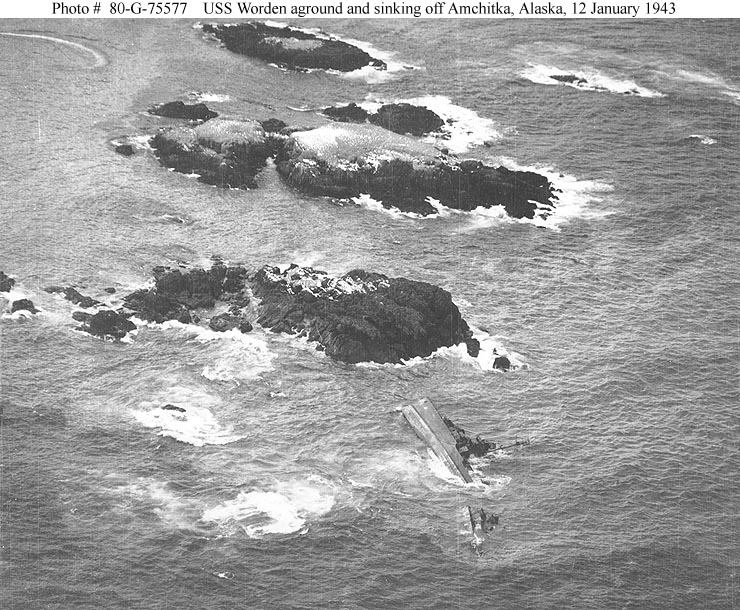

Worden gradually capsized to starboard, broke in two and settled on the rocks. Dewey pulled aboard 55 sailors and one soldier; two sailors were declared dead and were buried at sea; and one died aboard Arthur Middleton and was buried ashore. Some survivors were so stiffened by the intense cold that their oil- and water-soaked clothing had to be cut off. Others simply passed out in the rescue boats.

With a 60-knot arctic williwaw gale and dangerous swirling currents in Constantine Harbor, even the ship that rescued most of Worden’s crew, Arthur Middleton — manned by a U.S. Coast Guard crew — dragged anchor and ran aground the next night and remained there for 84 days — but not before rescuing 177 men from Worden’s.

From the official Coast Guard history:

When the distress call came, a Coast Guard landing boat under LCDR R. R. Smith, USCG, was rushed to the scene to render assistance. More help soon became necessary and Coast Guardsmen pulled their boats near to the vessel and sail “mountainous seas that threatened to swamp the landing boats” passed lines aboard to enable the men to slide down into the rescue craft.

The Middleton’s crew saved six officers and 171 men of the Worden’s personnel but 14 of the destroyer’s crew were lost. LCDR Smith; LT(jg) C. W. MacLane, USCGR; ENS J. R. Wallenberg, USCG; Russell M. Speck, Coxswain, USCG; Robert W. Gross, Coxswain, USCG; George W. Pritchard, Coxswain, USCG; and John S. Vandeleur Jr., Seaman 3/c, USCG, all received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, while four other officers and 42 enlisted men of the Middleton received letters of commendation from the Commander, North Pacific Force.

For all the efforts the Americans made to liberate Amchitka, the Japanese had decided that the island was not suitable as a military base and had abandoned it months earlier. Amchitka was deserted.

About 1 p.m. on 17 January 1943, the hull of the United States Ship Worden finally disappeared beneath the waves of the Bering Sea, eight years and two days after being commissioned. Of the dead sailors, 10 were never found and the partial remains of one unidentified sailor washed ashore about a month later.

Secrecy enveloped the disaster. On 10 August 1943, the navy depth-charged the wreckage to prevent any enemy salvage efforts of Worden’s advanced radar and communications electronics. Exactly two years later, on 10 August 1945 — 2½ years after the sinking — the Navy finally announced Worden’s loss. But the official public post-war combat narrative of the Aleutians campaign omits any references to Worden or the sinking.

As a final injustice, the official dates for earning a combat star for the Aleutians Campaign (engagement code P-20) are 26 March to 2 June 1943, despite the dangerous January landings and repeated air attacks against Amchitka beginning in January 1943. Worden sank during an official “war operation,” but the Aleutians operations were not a high priority in Washington; the entire campaign is now largely forgotten except among its few remaining veterans.

In April 1945, Commander Pogue was awarded the Bronze Star Medal by the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, H. Struve Hensel, for “…meritorious performance as commanding officer of the destroyer U.S.S. Worden.”

Even after the war Amchitka Island remained closed to the public and was eventually the site of several nuclear weapon tests. The island is still permanently off-limits to civilians. (A Canadian environmental activist group was formed in 1971 to protest the Amchitka nuclear tests; the founders eventually changed the group’s name to Greenpeace. They, too, were barred from landing on Amchitka.)

Today Worden lies in shallow water a few hundred yards southeast of Kirilof Point, at 51°24'35" North, 179°18'20" East . To get an idea of the many hazards in the area, see the interactive chart of Constantine Harbor or click on the chart image below.

A detailed chronology of the events of 12 January 1943 has been reconstructed from the ships’ logs.

For a detailed eyewitness account of the sinking and rescue, see Bob Low’s recollections and the official report of loss. The casualty list shows that of the 14 sailors who died, 11 went missing and were presumed drowned; two died, probably of exposure, aboard Dewey and were buried at sea the next day; and one died aboard Arthur Middleton and was buried in Alaska and later reburied in Texas. The names of some of the dead were badly misspelled in the official report, but our corrected casualty list and muster roll have been verified through other official records, including the Department of Defense’s authoritative “Missing in Action and Buried at Sea” lists.

Worden’s Final Minutes